Altogether Now: Rethinking Strategies for New Artists

As the music industry goes into freefall, which new models are worth pursuing?

A 12 minute read

WOMEX Guide October 2009

- world music

- music industry

- crowdfunding

- networks

- copyright

- streaming

- UK

- Senegal

- Kenya

- Mali

- South Africa

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Kaizer's Orchestra

- hip-hop

- norwegian

- punk

- Bryce

- Spotify

- Sellaband

- WOMEX

As professionals who take great pride in knowing what trends will hit the high street, many months or years down the line, 2009 marks the year that we in the music industry can really slap ourselves on the back. Financial meltdown has well and truly gone mainstream, and we saw it first.

But although world music execs have thankfully been spared the trauma of having to offload recently acquired, massively devalued luxury cars that has afflicted some of our friends over in the pop world, the symptoms are the same across the board: prolonged bouts of nervous head scratching over what will happen next, and where the dust will settle. Only one thing is sure: the money model that made the Western music biz go round in the 20th century is history.

“The most common refrain you hear these days is that ‘the recorded industry is broken’,” says creative consultant Andrew Missingham, author of a major recent strategy report for the national UK industry body, UK Music. The straws on its back are by now familiar: record sales in freefall, major retail outlets and music distributors going under, sync fees for licensing music to TV and commercials sinking rapidly... the list goes on. No matter how many times file-sharing sites like Napster, PirateBay or allofmp3.com are strong-armed into closing down or re-opening as reformed characters, online music sharing is not just unstoppable, consumers like it and view it as an inalienable right. Firstly it was hoped that digital sales from sites like iTunes would make up the numbers, but these sales now look to have peaked at far lower volumes than the old ‘physical’ sales charts.

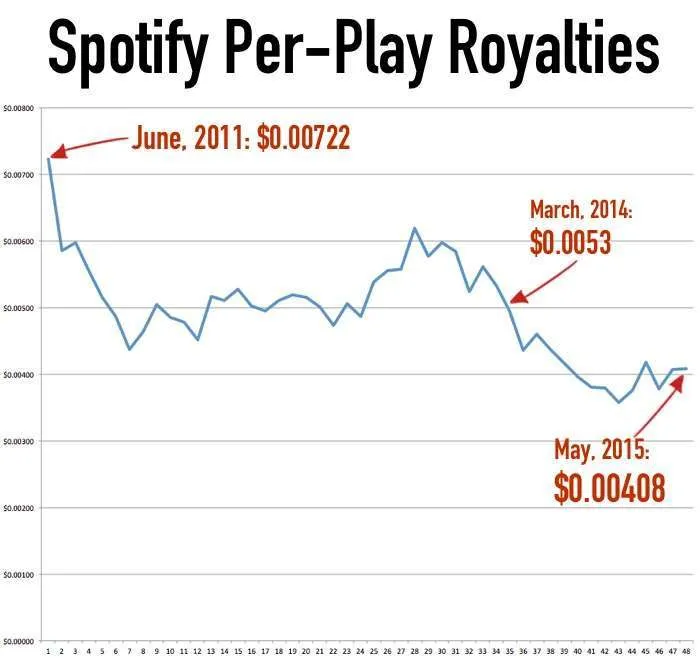

Another great industry hope was revenue from music social networks like Last.fm or advertising-based streaming services like Spotify and We7, but again the sums trickling down to artists are, so far, tiny in comparison to traditional media. With internet giants like Google’s Youtube adding to the pain in their current refusal to pay anything at all to artists or writers for showing their work, the basic principle of artist copyright as a money generating device is starting to look shaky indeed.

The main challenge for the world music industry is the same as it is for everyone. How can artists build a sustainable career without income from recordings and record company advances?

Part of that answer might lie in parts of the world where recording royalties and advances have never been a part of the local music scene. Groove Armada’s recent exclusive deal with Bacardi – a drinks company with limited experience in music – will be familiar to musicians in Russia, where recordings are often financed by commercial sponsors, and CDs can look like flyers covered in logos. Radiohead’s internet release of In Rainbows for free to generate maximum publicity will be familiar to artists in Africa and elsewhere who know that a high public profile in the local marketplace means more demand for live shows and better paying gigs.

So what does all this mean for new artists, where traditionally record companies have had to work hardest – and invest more – in kickstarting their career? Several players have been coming up with interesting ways of helping unknown talents get out there, and make their mark. The most radical comes from AfricaUnsigned.com, where founder Pim Betist is out to prove that if the music industry can get over its natural aversion to sharing, and see that sharing can also mean reduced outlay and risk, everybody can benefit.

I was working for Heineken and Shell but as a music fan I felt constantly frustrated by the music I was being fed by mainstream media. At the same time, I would consistently hear live acts I thought were much better. When Myspace launched, and I saw how bands were accumulating friends, the thought struck me: what would happen if each fan, instead of just being a ‘friend’, chipped in ten dollars?

Betist’s first new model Sellaband was born, and with it the idea that music lovers – the same people who will go on to buy a record – are both the best A&R men and women around, and potential investors who can earn money through helping an artist to finance their first album without the artist being forced to sign away their rights in an exploitative record contract.

The website went live in August 2006, and two months later, the first band hit fifty thousand dollars (of investment from fans) and recorded their album. To date thirty-two bands have raised that much.

After two years on the Sellaband team, Betist became disappointed at the type of bands that were coming to the site – “mainly mainstream-style rock and guitar bands” – so his newest venture is much more focussed and selective. AfricaUnsigned takes the fan-as-investor model of Sellaband, but with talent contests, marketing and a live agency all added to the mix.

Bryte, a Ghanaian rapper on AU Initially established in five countries - Senegal, Mali, Kenya, Zimbabwe, South Africa – a combination of Pop Idol style voting and a panel of star judges, including Baaba Maal, Oliver Mtukudzi and Tony Allen will help to whittle hundreds of entries down to five per country, and then these twenty five artists will all be presented on the AU site. Artists who raise ten thousand dollars to make their first professional EP sign a non-binding record and publishing agreement with a fifty-fifty artist profit share. “Our contracts are fairly cuddly,” laughs Betist. “We have completely diversified our risk, and we don’t need to pay any advances.”

While not as radical as sharing profit with fans, Update: crowdfunding is evidently a hard gig. AU has now become an interactive agency working with brands and African music. another interesting way in which parts of the music industry are using networks to help break the mainstream media deadlock also comes from the Netherlands. For Peter Smidt from Eurosonic Noorderslag, the key to helping new artists –particularly from non-Anglophone countries who can find it much harder to break into mainstream media – is closer industry collaboration between media, festivals and record companies. One key joint initiative is The European Talent Exchange Programme (ETEP), run by Eurosonic Noorderslag in cooperation with the European Music Office, Sena Performers, Yourope and the European Broadcasting Union amongst others. For new European artists, ETEP is an effective means of bypassing traditional barriers to mainstream exposure and plugging straight into a network of big European public broadcasters and major summer festivals like Glastonbury and Lowlands.

Traditionally an artist manager would first look for a record deal, and if he or she couldn’t get distribution in a certain territory then it was very hard to get festivals or airplay. But now bands like The Kaizer’s Orchestra, who sing in a Norwegian dialect, can get into the ETEP framework and turn around the traditional model: first they tap into radio exposure and summer festivals, and then if a record company knows in January that a band is guaranteed coverage in the summer, they’ll get released.

Behind the music:

Behind the music:

What it costs European acts to sing in their own languages

Despite the explosion in the sheer availability of music over the internet, Smidt sees that it is getting increasingly hard for new artists to break through. “It is curious that while audiences are more open now to sounds that are not in the top 40, mainstream media seems to be getting increasingly narrow in its focus. So while ETEP is helping, we have a lot more work to do to get music from countries like Spain, Italy and Central and Eastern Europe out there to a wider audience. But the onus is much more on the artist now to create more of their own platforms. Careers start these days from a live music base – the other parties come later.”

It’s not just different parts of the industry which are learning to communicate better: as record company support dries up and the industry-wide focus shifts onto live, promoters are joining forces in networks too in order to share costs and raise their collective clout.

Live Boutique started four years ago, when two French promoters created asked us join their collective website. At that time the crisis was just starting – record companies were investing less and less in marketing and tour support, and we felt it we needed to find a collective answer to the problems we were facing. So we decided to put together a company to share costs and to invest together in advertising and promoting up and coming acts.

Today Live Boutique is a collective of twelve live agencies with a roster of three hundred artists performing six thousand shows a year. Their joint promotions of new acts have been so successful that they are even looking into buying a venue together to reduce their expenses. This strength in numbers, coupled with the new commercial importance of performing live for the industry as a whole, means that the industry is being forced to work together to break new artists.

A few years ago we were considered as peanuts by record companies. Since the crisis started, there is no plan that gets put together for a new act without meetings between the record company, publishers and promoters. This is a big change: teamwork. Now every part of the puzzle – record company, promoter, publisher, manager – is just as important. My feeling is that a project that will be successful is one with a good team and good synergy. If an act has a strong, professional entourage, then you have a chance.